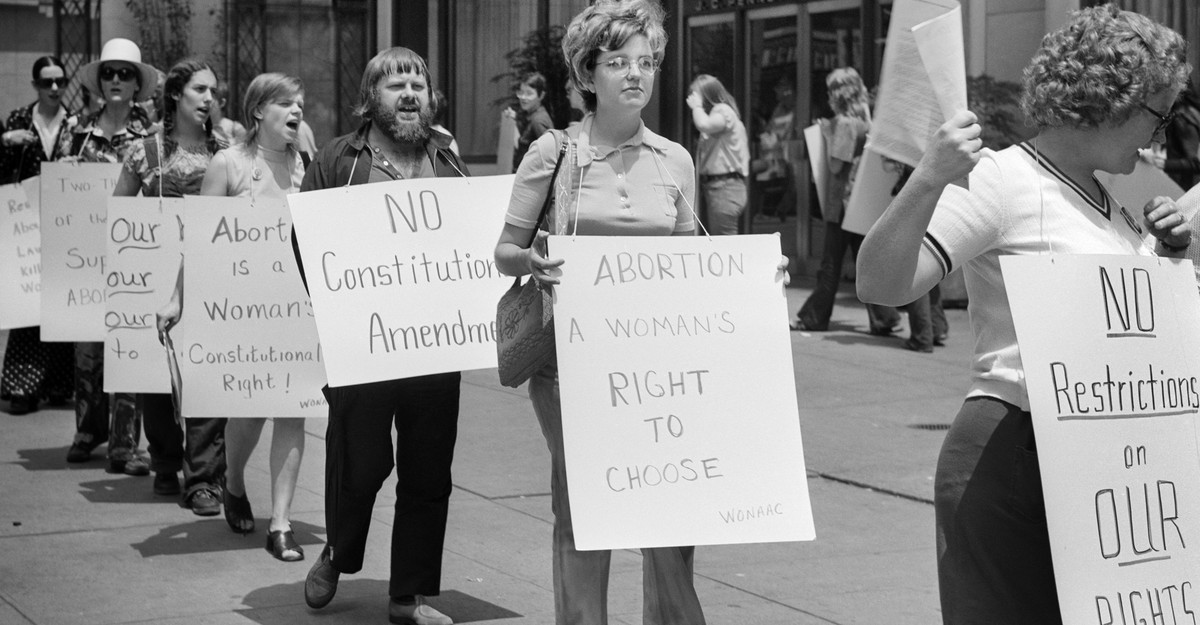

My world has always been conditioned by an automatic assumption of reproductive rights that my mother, the writer Erica Jong, did not have when she came of age. I was born in 1978, five years after Roe v. Wade. Like most women under 50, under 60 even, I find it hard even to imagine what life was like for women in those pre-Roe years. Yet that is the world we’re going back to if Justice Samuel Alito’s leaked draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization is any guide to the Supreme Court’s final ruling, now due any day.

My mother would tell me stories when I was growing up about her life in that pre-Roe world. She described a place where a man could put his hand on your butt and you were expected to treat it as a hilarious joke, to be a good girl, to be nice, however put upon you were. She told me about how anxious she was eating alone in restaurants, because she’d been told that people might think she was a prostitute. About male teachers making sexual overtures, chasing her around a table, asking for oral sex.

Mom was an undergraduate at Columbia and Barnard in the early 1960s, and got her master’s at Columbia in 1965. My mom, I always figured, was a bit creative in her retellings, but clearly even the prestigious institutions she attended were at best sexist, at worst downright predatory.

In those days, young women were supposed to move seamlessly from their father’s house to their husband’s. Mom married the first person she had sex with, her college sweetheart, or so she told me. But then, not long after they wed, he had a psychotic episode and went back to live with his family in California. Divorced in her early 20s, Mom promptly remarried. Because that’s what one did—you had to have a man to secure your right to belong in American society in pre-Roe America. Her second husband was a psychiatrist, who was soon drafted to serve in the Vietnam War. Mom would write about him in her novel Fear of Flying, and then leave him for husband No. 3, later my father.

The year the Roe judgment came down was the same year Fear of Flying appeared and made her famous. According to The New York Times, “The novel was hailed by many (not all) in feminism’s second wave as a pathbreaking achievement for female self-expression.” It was, of course, a largely autobiographical novel, a truth my mother alternately denied and embraced depending on her mood—or perhaps depending on what seemed permissible. In a 1968 poem, my mom wrote about what was valued then in the literary world: “The ultimate praise is always a question of nots: / viz. not like a woman / viz. ‘certainly not another poetess.’” In other words, anything but the female or the feminine.

Pre-Roe life was hard for women in almost unimaginable ways. In a short memoir of that period, “My Abortion War Story,” the author Joyce Johnson wrote about how hard it was even to get a diaphragm in those days. She tells the story of a friend who “had to purchase a wedding ring at Woolworth’s before going to the Margaret Sanger Clinic. There, she’d filled out a questionnaire about her sexual habits, those of her ‘husband,’ and the frequency of their intercourse, nearly every word of it made up.” Birth control was for married couples only.

I recently spoke with Johnson, now 86, about life back then. “Sex seemed very freighted with risk and meaning,” she said. “You didn’t go to bed with people lightly. One sexual encounter could ruin your life.” People used condoms, but they were unreliable. And as for getting an abortion? “It was much harder to get information back then. You were totally dependent on your network. It was almost like sending out a chain letter.”

A great deal changed with the pill, but it didn’t become widely available until the mid-’60s, after Griswold v. Connecticut, the Supreme Court ruling that allowed only married couples to use contraception. By 1965, 40 percent of young married women were on the pill. But it wasn’t until Roe that women, married or not, had full reproductive freedom.

Until then, one bad decision could alter your life forever. Representative Barbara Lee has related how she had an abortion as a 16-year-old in the ’60s: “As a teenager, there were very few options. So I had to leave the country, had to go to Mexico to have an abortion, which was risky, because they weren’t legal there either. Fortunately, my mother’s friend knew a clinic, and yes, it was a clinic in a back alley that had a good reputation, and that’s where I went. And fortunately, I survived. But during that period, so many African American women died from septic abortions.” In the past three decades, septic-abortion deaths have declined worldwide by about 42 percent, but as The Atlantic’s Olga Khazan has noted, “Unsafe abortions are more common in countries where the practice is illegal.” Even now, Black women are more than three times more likely to die in childbirth than white women.

In 1975, Mom told a Playboy interviewer that she foresaw a world in which women would be “in a position to choose men not out of desperate need for a social rudder or an economic supporter but out of their own desire for companionship, for friendship, for love, for sex. That time has come for only a fraction of women, self-supporting professional women. It has come for me. But when it comes for most women, we’ll see great changes, because women will not put up with the stuff they’ve put up with for centuries.”

The right to privacy that gave women autonomy under Roe is not the same as equality, argues the cultural historian and lawyer Linda Hirshman. “There was a hypothetical pathway to have abortion play a role on the road to women’s equality, but it would have required that the decision be made on the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” she told me. “That was Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s plan, but that’s not what happened. Instead, Justice [Harry] Blackmun put it in the line of cases based on the right to privacy rather than women’s equality.”

But Roe did prove a landmark on the way to greater equality. In 1974, Congress passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which allowed women to get a credit card without their husband’s involvement. In 1977’s Barnes v. Costle, the D.C. Circuit ruled that sexual harassment was a form of sex discrimination. Also in 1977, Alexander v. Yale became the first use of Title IX to pursue sexual-harassment cases. In 1978 came the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which was appended to the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Roe was the crucial win that saw not only this cascade of laws but also a decisive cultural shift toward treating women as sentient beings. The message was clear: Being able to control one’s fertility leads to being able to control other aspects of one’s life.

That post-Roe optimism was infectious. Mom told Playboy of her delight at the end she saw coming to women’s “being nursemaids to their men; taking what is dished out to them; being chief cook and bottle washer, baby sitter, nanny; entertaining the husband’s guests, the whole servant-master relationship.”

Today, nearly half a century later, my mom has dementia. She remembers things, then forgets them, and we go round. I’ve told her more than once about the imminent risk: “Mom, the Supreme Court is going to overturn Roe.”

“They are?”

There are a lot of things that I don’t want my mom to forget, a lot of her that I don’t want to be shaken away like a face on an Etch A Sketch. But Roe … I may not be able to remember a pre-Roe America, but, for her sake, I hope my mom does keep forgetting that we are entering a post-Roe America.

"about" - Google News

June 22, 2022 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/WCXbUuw

What My Mom Told Me About America Before Roe - The Atlantic

"about" - Google News

https://ift.tt/dLvqk3T

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "What My Mom Told Me About America Before Roe - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment