The tumultuous nature of the last year has led each of us to find our own particular cultural coping mechanisms. One of the key ones for me has been reading the novels of Jane Austen. After writing her work off in my younger days as simpering and convoluted, featuring heroines with whom I could never empathise, I have now found myself drawn to her work in a way I never have been before.

More like this:

– The most joyful books ever written

– Why funny books can also be serious

– The Jane Austen novel you didn’t know

Sales figures would suggest I'm far from the only one relying on her humour and heart to get me through these strange days. In the UK, as Kiera O'Brien, charts and data editor of the Bookseller, notes, Austen experienced a sales rise of 20% in the UK between 15 June and 7 November last year, compared to the same period in 2019. Last December saw the 245th anniversary of her birth and her popularity only seems to be getting stronger.

Glossy Austen adaptations such as 1997’s Emma with Gwyneth Paltrow have been hits – but her writing is much more steely than these often suggest (Credit: Alamy)

But why should her novels be suited to this pandemic era? On one level, it might seem obvious: such is the image of them crystallised in the public imagination by many glossy TV and film adaptations, they would seem to offer the perfect romantic escapism. (Indeed, it seems no coincidence that the TV mega-hit of the moment, Netflix's Bridgerton, is a romantic drama set in Austen's Regency period, albeit with a decidedly more cartoonish and sexually-explicit sensibility). However when you actually dig into the writing, you find Austen offers more unexpected consolations. Beyond their preoccupation with love and romance, there is a layer of steel and a celebration of resilience in her books that may well inspire us as we read them in these deeply uncertain and circumscribed times.

A model of perseverance

Austen's own life was a lesson in forbearance. She published her six celebrated novels in the space of seven years and died at the age of only 41. "On paper it looks like she has a secure life but she is sent off to boarding school twice and she almost dies," says Dr Helena Kelly, author of Jane Austen: A Secret Radical. "In the first the whole school got typhus. Her aunt who came to nurse her died. Just imagine the psychological harm of that happening to you – and then she got sent off again."

The general state of instability Austen suffered for much of her life is replicated in many of her heroines. In 1800, when she was 25, her rector father retired, passing the parish over to his oldest son "which was really unusual", Kelly says; Austen and her parents and sister Cassandra spent the next eight years travelling between increasingly small properties in Bath, relatives' homes and seaside resorts. "It's a time we think she didn't write very much because she was all over the place," Kelly says. "They move back to Chawton, Hampshire in 1809 and it's only when she's somewhere psychologically secure, [in] a house she knows won't be taken away from her, that she starts publishing." Displacement and the fracturing of family life arises in much of her work, such as in Sense and Sensibility which begins when the Dashwood sisters and their mother must leave their family home and are then stripped of their inheritance from their father by their half-brother and his manipulative wife. "Austen is very, very precise about money in her novels," says John Mullan, author and professor of English at University College London. "She knew what financial insecurity was like."

The sensation of feeling both trapped and surrounded by familial friction is also a prevalent element in Austen's work – and is something that many of us can relate to now especially when, as for many of her protagonists, walks are often the most liberating thing on offer. Pride and Prejudice's Elizabeth Bennett appears to strive for freedom by striding about the countryside and getting muddy, enjoying peace away from her overcrowded family life. "There's a constant low-level psychological stress that all her characters are under," Kelly says. "On the whole, they are quite good at just getting on with stuff even if there's not much to get on with." She believes that Austen was also pioneering in the way she showed families as imperfect. "Before Austen, mothers and fathers tended to be dead or perfect and living in bliss together and in her work she makes this clear it is not the case."

The young Austen (seen here played by Anne Hathaway in the 2007 film Becoming Jane) endured many false starts in her writing career (Credit: Alamy)

Meanwhile Austen's journey to publication can also be seen as a lesson in resilience, paved with rejection and false starts. After starting to write at around the age of 12, she began doing it seriously in her 20s but did not get published until her mid 30s. When she was aged 22, in 1797, her father sent off an early draft of Pride and Prejudice to the London publisher Cadell & Davies, which was rejected curtly by return of post, while six years later, another novel named Susan was accepted for £10 by Crosby and Co but never published by the London firm. "The disappointment of that must have been absolutely crippling," says Kelly. "It's clearly something she [had] been dreaming about for years and years." In 1809, Austen wrote an aggrieved letter to Crosby and Co – "not a template of what to write to your publishers", according to Kelly – which proved ineffectual. Then in 1816, just a year before she died, she finally bought the manuscript back – leading to it being published posthumously as Northanger Abbey (accompanied by a disgruntled 'Advertisement by the Authoress' lamenting the earlier non-publication). "It took a lot of grit to carry on especially when her brothers wanted her to look after their motherless boys," Kelly says.

Her heroines' growth

Austen's heroines are similarly often required to persevere, though more stoically, suffering in silence after believing their chance of happiness has been lost forever. The moment when Elinor Dashwood steels herself before seeing her love Edward Ferrars, wrongly believing he has married another – "I will be calm, I will be mistress of myself" – is both heartbreaking and inspiring; a strength of character rendered particularly powerfully by Emma Thompson in her performance in the 1995 Ang Lee film adaptation that she also scripted. In Persuasion, protagonist Anne Elliot is confronted with Captain Wentworth who she loved and rejected nine years ago, and apparently fails to recognise her because she is so changed ("so altered that he should not have known her again"); she is mortified, as she still loves him, though she tries to hide all display of emotion. Some claim this is Austen's most romantic novel, partly because of how Anne learns to reveal her real feelings so that Wentworth can "know" her truly, leading to one of the most moving literary denouements in which he tells her: "You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope".

"If you look at every single one of Jane Austen's heroines, they get to some stage of the story where they think they're not going to get the person they want, " says Mullan. "In several of them, the central character becomes convinced that the man she loves is going to marry someone else even if the reader knows better. In that simple sense, these are stories of not just getting what you want but accepting that happy endings might not be available to you. So self-pity is not an option."

Which brings us on to the emotional growth of Austen's characters – another facet of them that can prove inspiring to us at a time of uncertainty when we are perhaps re-evaluating what really matters. Psychologists such as Angela Duckworth, author of Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, talk of a "growth mindset" – a way of thinking founded on the principle that life should be lived as a constant process of adapting to challenges and accepting and learning from your mistakes. It's a mindset that many of her heroines acquire: as well as dealing with insecurity over money and status, they often contend with a sense of shame over their past actions – before they learn from it and are changed by experience.

Spoiled, pretty Emma, for example, is so bored and cosseted in her small village that she takes on people as 'projects' and mocks characters like the kind and relatively impoverished Miss Bates, before learning the error of her ways. "A key moment in most of the novels is the moment when the heroine realises she has been wrong about another character," says Dr Gillian Dow, associate professor in English at the University of Southampton. "We feel Emma's shame after mocking Miss Bates on Box Hill, because we live the event via Emma's thoughts, and Austen shows it to us; it's key to understanding how Austen develops her characters. Similarly the moment when Elizabeth Bennet realises she has been wrong about Wickham, and therefore wrong about Darcy, is a pivotal moment in her personal development: she 'grew absolutely ashamed of herself', [Austen writes], and we feel ashamed along with her."

Sense and Sensibility’s most heartbreaking moment is when Elinor believes Edward Ferrars has married another – as depicted by Emma Thompson in the 1995 film (Credit: Alamy)

Arguably we feel their emotional transformation so painfully because of Austen's pioneering use of the authorial voice, which inspired writers such as Gustave Flaubert, Henry James and Franz Kafka. Her particular kind of narration allows us simultaneously to live in the mind of the characters but also share in the knowledge, as suggested by the narrator, that the characters' beliefs are often wrong. "She does this incredible thing where she invents ways of writing narrative so we can see characters and the errors they make but also live inside their thoughts," Mullan says. He believes, above and beyond the themes in her writing, that it is her revolutionary writing style which really resonates with modern readers. "Before [her], [novels had either been] first or third person and she perfected free, indirect style which combined the two… you read the novel through [the characters'] eyes so it's a really extraordinary technique which no one had really done before."

It's a style that allows for a particularly intimate reading experience, which author and Austen expert Dr Paula Byrne believes is one of the reasons many refer to the author simply as 'Jane'. "Sometimes I find it patronising but I think it's also because people do genuinely think of her as a friend. I find this psychologically interesting – all these brilliant things she's doing in a technical sense, make you think 'I feel really relaxed and comforted'."

Byrne is so interested in the comforting aspects of Austen that she is devoting a book to the subject. "I've been trying to unpick why do we return to her, why is she the comfort read and people say she's like crawling under a warm duvet on a cold night, there's something really comforting about her books but I'm really interested in unpicking what that means."

Austen on prescription

In fact, Austen's writing is so strongly associated with providing solace that, as Byrne discovered, she was prescribed to World War One soldiers suffering from severe shell-shock or what we would now know as PTSD: in a letter titled The Mission of English Lit to the Times Literary Supplement from 1984, Martin Jarrett-Kerr wrote: "My old Oxford tutor, H F Brett-Smith, was exempt from military service; but was employed by hospitals to advise on reading matters for the war-wounded. His job was to rate novels and poetry for the 'fever chart'. For the severely shell-shocked he selected Jane Austen."

This wartime association is celebrated in Rudyard Kipling's 1924 short story The Janeites, about a group of soldiers who bond through their love of Austen, with the protagonist discovering her work whilst in Bath recovering from trench foot ("there's no one to touch Jane when you're in a tight spot.")

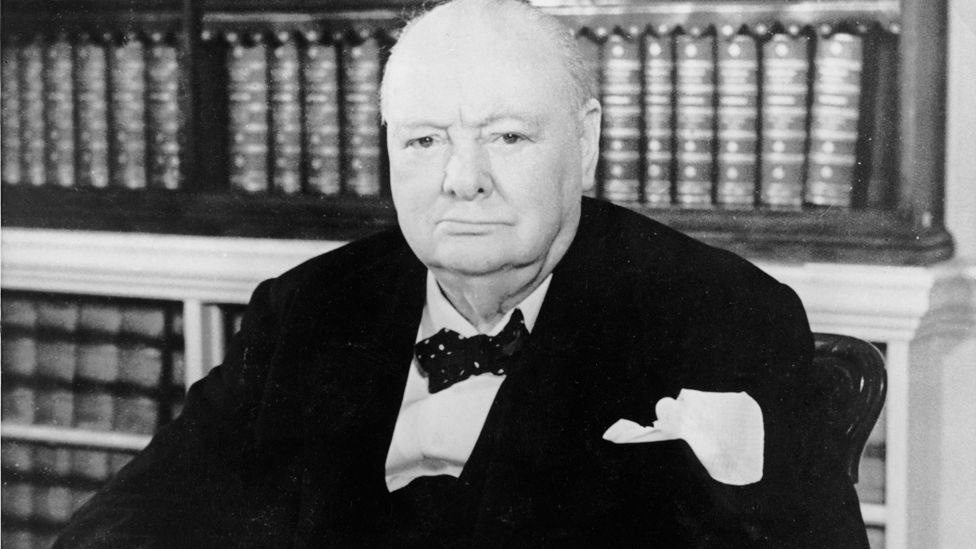

Byrne became fascinated by soldiers' reading of her whilst researching her book The Genius of Jane Austen; in the very thick of World War One, she learned how they would keep classic texts in their pockets while in the trenches, and discovered that Winnie the Pooh author AA Milne had bonded with fellow soldiers over his love of Austen during his time fighting. Fellow Austen fan Lance Corporal Grainger followed Milne out on to the front line just to check on the author after they had become friends over their shared interest in the books – a gesture described by Milne in his memoir as "the greatest tribute to Jane Austen that I have ever heard." Another notable figure who relied on her in times of war was the bedridden Winston Churchill in 1943, who was consoled during illness by having his daughter read Pride and Prejudice to him.

Winston Churchill is among those who have been consoled by Jane Austen in times of trouble (Credit: Alamy)

Back in the present day, meanwhile, Dow has been made alive to the therapeutic power of Austen through her teaching of a free online course Jane Austen: Myth and Reality on digital education platform Futurelearn. "In March we were joined by an ICU nurse from the USA, and many learners announced they were self-isolating, on furlough, recovering from illness, or seeking distraction. 'I shall miss my lockdown afternoons with Jane', wrote one participant at the end of the course," she says.

Each reader has their own particular reasons to find Austen a tonic, of course. Kelly, for her part, believes there is something especially soothing about the way Austen's novels tend to span a calendar year: in employing that timeline, they evoke the fact that "the sun will come back and life will improve", she says. Or as Lady Russell says in Persuasion: "Time will explain". Meanwhile, for Byrne, there is a restorative power in the very rhythm of Austen's sentences. "The way that she writes has a slowing down effect which encourages slow reading, you can't really read her quickly," she says.

Byrne uses Austen in her non-profit, ReLit, established in 2016 to promote the complementary treatment of stress, anxiety and other conditions through slow reading of great literature in schools, prisons, hospices and for healthcare workers suffering burnout. "Sometimes I'll just read a passage for meditation purposes from Persuasion or Mansfield Park when I visit schools and prisons, and I'll say: 'Just think about how this makes you feel'", she explains.

It feels shameful to admit that I, myself, failed to read Austen until I was 30. But on finally reading and enjoying the richness of her writing with its mixture of social satire, poignancy and dawning epiphanies, I have secured a safe haven to which I will return to for the rest of my life. The key to Austen for me is that she simultaneously comforts and challenges us, embracing the dark and lonely aspects of life but with a lightness of touch and humour much-needed in difficult times.

Mullan reveals he, too, did not always take to Austen and that it was through teaching her work that he found her charms. "I was a solemn male teenager. I foolishly thought, 'Oh these novels are the same. They're about girls finding a husband'. I was shown her genius by lots of now forgotten students who responded to her ingenuity with their own insights and it dawned on me how complex and endlessly re-readable these apparently simple stories were."

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"about" - Google News

February 03, 2021 at 07:04AM

https://ift.tt/3pVAAEJ

What Jane Austen can teach us about resilience - BBC News

"about" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MjBJUT

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "What Jane Austen can teach us about resilience - BBC News"

Post a Comment